Sharing Your Impact

April 27, 2024

Greetings from the South Dakota Humanities Council! We are filled with gratitude for the opportunities your contributions have created, and as we reflect on the impact of your generosity, we’re excited to share with you what your steadfast support has done to fuel the SDHC mission to enrich lives through the power of humanities.

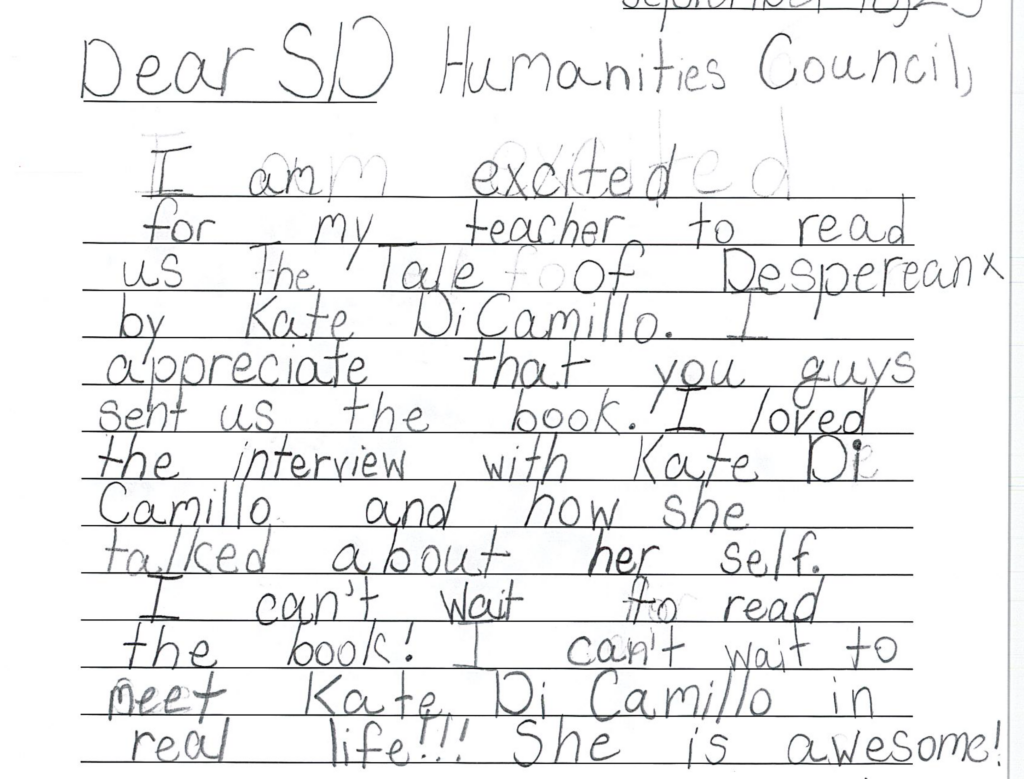

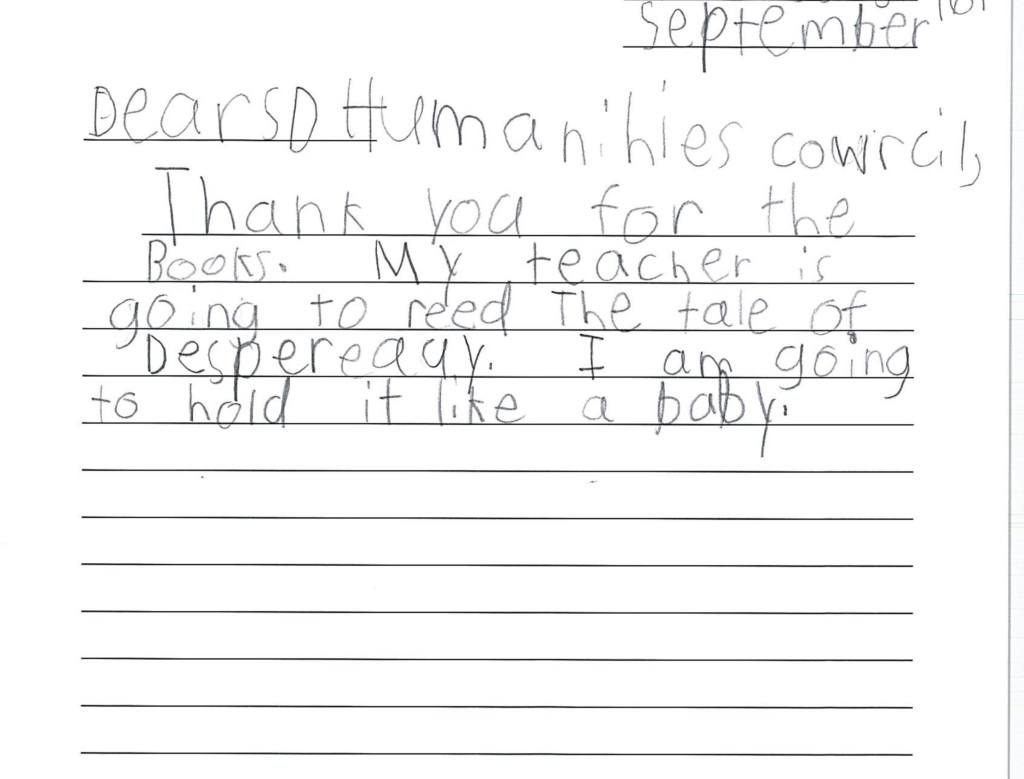

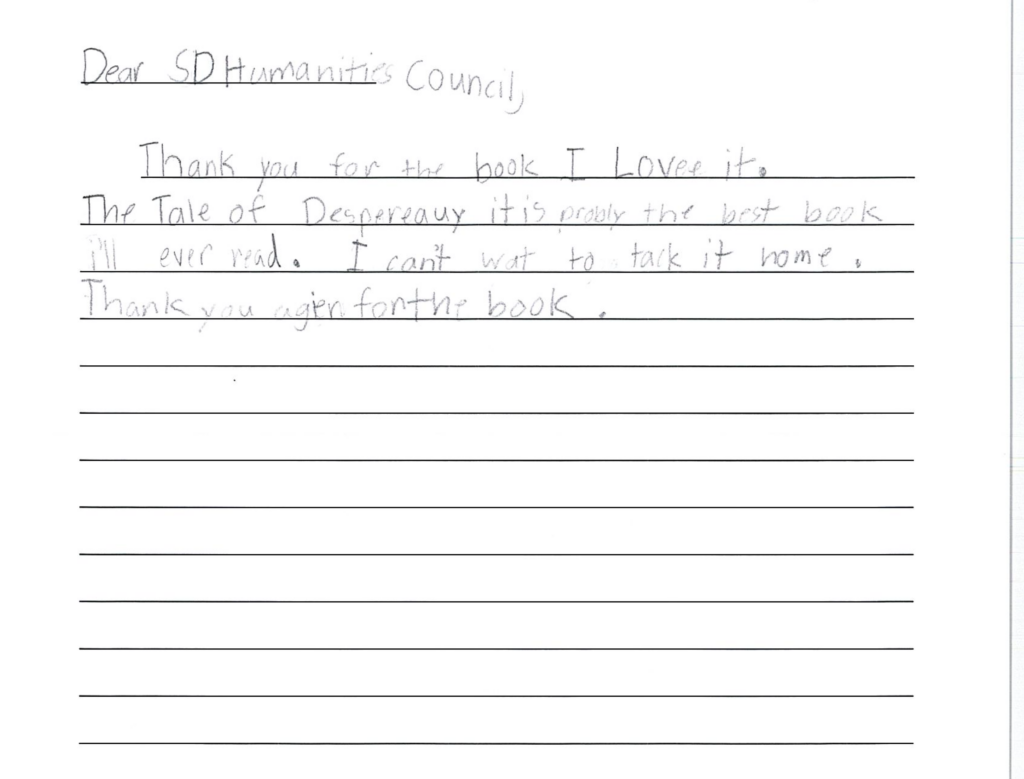

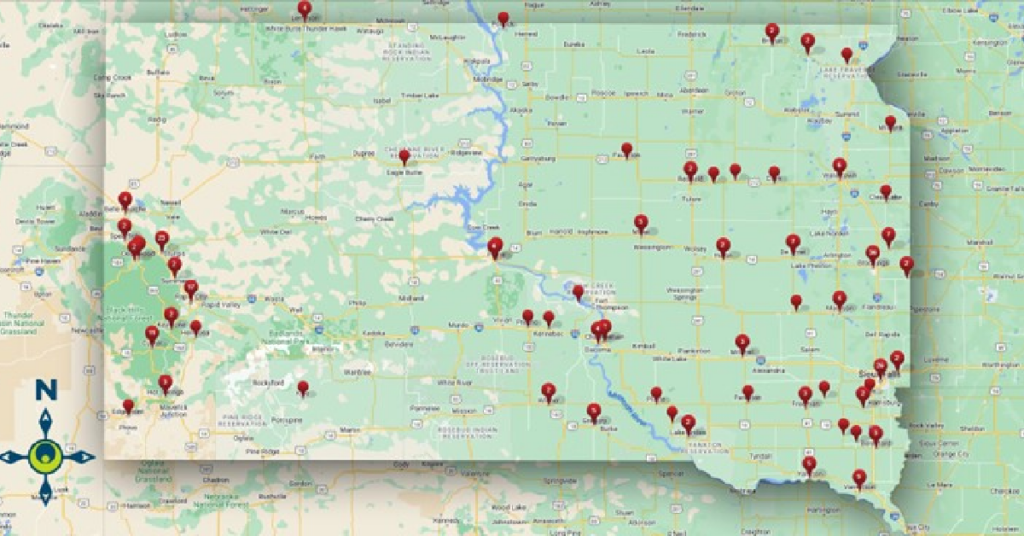

Young Readers Program: This program focuses on igniting a love of reading by promoting literacy engagement among our South Dakota youth. Last fall, we achieved a monumental Young Readers goal of successfully delivering over 14,000 books to every third-grader across South Dakota. As Miss South Dakota Miranda O’Bryan noted, “They have access to [the Young Readers] book that is their very own so that it can inspire them.” For instance, we’ve displayed these several student’s heartwarming letters in the office expressing their joy and gratitude for the books, which are their treasures.

Click Images to View Letters

Festival of Books: Our annual Festival of Books, a unique event that brings diverse authors and engaging literary discussions to our state, has not only inspired a passion for reading and lifelong learning but has also sparked personal growth and development. As one participant shared, “The festival opens my mind to new voices/ideas, inspires me in my own creative endeavors, and helps me connect with people on the other side of the state and beyond.” This event, made possible by your support, is a testament to the power of literature and the impact of our collective efforts.

Programs:

Veterans Writing Workshops: In 2017, we launched the Veterans Writing Contest. In 2024, we plan to enhance this program by offering a series of summer writing workshops on each side of the state. Our goal is to support veterans in a larger capacity by providing networking and storytelling opportunities. We will also invite them to attend the Festival of Books, during which they may expand their personal networks and share their stories with a broader audience

Brainstorming the Human Connection: Our weekly online conversation program unites people through genuine reflection on diverse topics, including culture, language, history, arts, music, books, film, travel, relationships, technology, medicine, and philosophy. This program has been instrumental in fostering understanding and growing community. One participant noted, “I really like this program. It’s one of the ways I try to keep up with what’s happening in my home state.”

“We the People” Column by David Adler: Our column “We the People” by David Adler promotes civic education and encourages a deeper understanding of our Constitution, fostering civil discourse and appreciation for democratic principles. A participant shared, “I appreciate listening to David’s insights and anecdotes about the founding of our Constitution.”

Speakers Bureau: Our multifaceted speaker’s program offers opportunities for communities across South Dakota to invite a scholar to speak on a humanities subject. One such opportunity supported writing workshops for seniors, providing a therapeutic outlet for emotions and preserving valuable memories. A participant shared, “Strengthened my approach to writing,” and another expressed, “I learned that it’s never too late to begin writing – again. And ten minutes a day can add up.”

Humanities Grants:

Major & Mini Humanities Grants: Our grants emphasize collaboration among cultural, educational, and community-based organizations and institutions in order to serve South Dakotans with public humanities programming. An activity that enriched our community was a noted author, poet, and veteran, Brian Turner, who addressed the Augustana University campus, delivering a major poetry reading. He taught four courses for students and ran a creative writing workshop for veterans. Turner pointed out that the composition of the audience was atypical, with an equal mix of students and veterans. One participant remarked, “This was an incredible, deeply human reflection on the Iraq War exactly 20 years after it began. Brian Turner is a wonderful speaker and poet.”

Your continued support enables us to shape a brighter future for generations to come. We are honored to have you by our side as we continue our journey of enriching lives through the humanities and building a stronger, more connected community. Together, we are shaping a brighter future for generations to come.

Thank you for believing in the power of the humanities and for being a champion of positive change in our community!

Learn more about humanities programming in South Dakota by signing up for SDHC e-Updates!