Caring for Seeds and Each Other

September 23, 2023

NOTE: A version of this story appears in our 2023 South Dakota Festival of Books guide, produced by South Dakota Magazine.

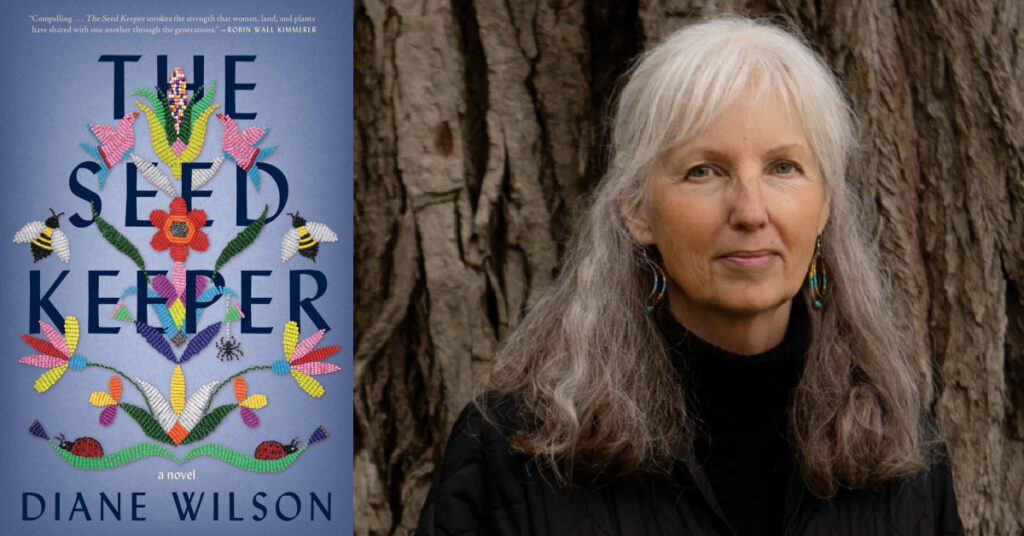

Diane Wilson will speak this morning (Saturday, Sept. 23, 10:15 a.m. MT) at the Festival in Deadwood and will close out her One Book Author Tour tomorrow (Sunday, Sept. 24, 2 p.m. MT) at the Piedmont Valley Library.

The Dakota Commemorative Walk, held every November, retraces the steps of 1,700 Dakota women, children and elders who were marched 150 miles from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling following the 1862 Dakota War. It has been called Minnesota’s Trail of Tears. But powerful stories have survived that heartache, including one that inspired Diane Wilson’s The Seed Keeper, the 2023 One Book South Dakota.

Wilson joined the march one year and heard another walker talking about the original displaced Dakota women. Because they didn’t know where they were going, they didn’t know how they would feed their families, so the women sewed seeds into the hems of their skirts and hid them in their pockets. “Even when families and children were hungry, they protected those seeds so there would be something to plant the next season and for future generations,” Wilson says. “That story just hit my heart. The courage and sacrifice they made in that moment to protect those seeds demonstrated what we need to be doing today to make sure we have these healthy foods.”

The story came at a serendipitous time. Wilson was working on a memoir about her mother, who grew up in a Dakota family in South Dakota and attended boarding school on the Pine Ridge Reservation. She had also become aware of an effort near her home in Minnesota to preserve heirloom seeds.

It all coalesced into The Seed Keeper, the story of seven generations of a Dakota family that endures war, the boarding school era and the hardships of adjusting to life in an increasingly non-Indian society — all while protecting a precious cache of seeds.

Each family member’s reverence for nature and the environment is tested as agriculture becomes an industry fixated on yields and profits. “You get to see how these seeds go from being protected by Dakota women during the war and as each generation progresses, those seeds evolve in their relationship with people,” Wilson says. “By the time we get to 2002, we have genetically modified seeds. My hope was that by telling this long story across generations that people would see how our relationship with seeds has changed, and then we can have a conversation about what that means and what the consequences are.”

Discussion groups have lauded Wilson’s storytelling and her generational approach. In her travels, she says audiences are just as focused on how they can become better stewards of the land. “A lot of people feel paralyzed. They don’t know what to do,” she says. “They feel helpless because the headlines are filled with new and dire predictions. What has been heartening to me when people read the book is the idea that we still have a responsibility to all of our relatives — birds, animals, plants, water — to take care of them. So what can you do in your life, your yard, your community that can make a difference? I enjoy brainstorming with people from the teachings in the story. What happens when you actually take care of those seeds? That’s the way we are meant to live, as relatives taking care of each other.”

Learn more about humanities programming in South Dakota by signing up for SDHC e-Updates!