South Dakota’s Prairie Poet Laureate

April 20, 2024

NOTE: This piece was written by Julianne Hanson, PhD, of Spearfish. With her permission, SDHC is sharing it in honor of National Poetry Month.

Most locals have heard of the first South Dakota Poet Laureate, Badger Clark, whose term was from 1937 to his passing in 1957. Clark was known for his ardent descriptions of “buckaroos” and the western landscapes they worked and traveled.

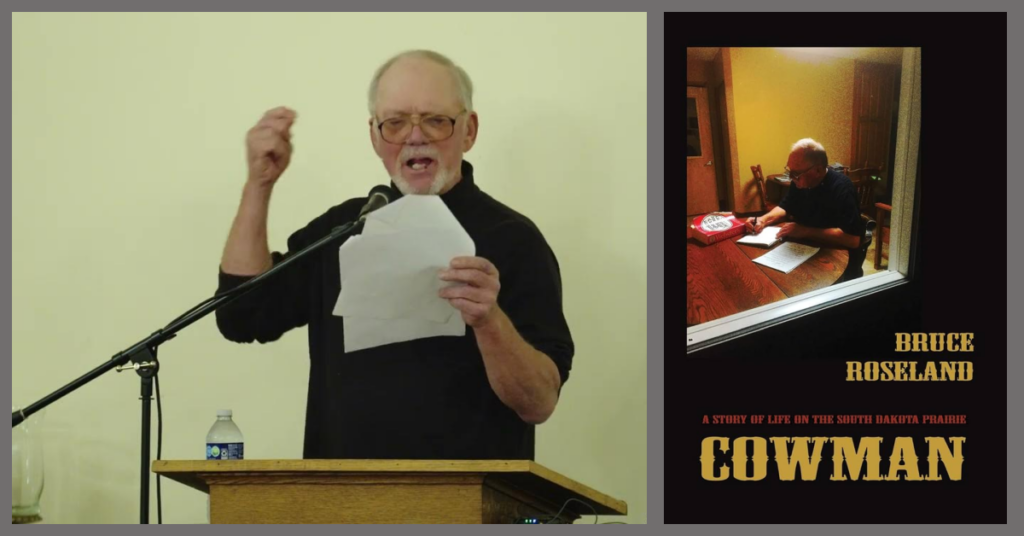

Bruce Roseland is South Dakota’s eighth Poet Laureate. His term runs 2023-2027. He has been compared to Clark in their mutual celebration of lives lived in the wide open. He is a fourth-generation rancher in north-central South Dakota, near Seneca, population 18.

Roseland began writing seriously in the early 2000s as a means of recording life events he feared might otherwise be forgotten. “My great-grandfather didn’t write down any of his experiences,” he said. “I’m sure he would have considered his life ordinary. But I would love to have known about a day in his life. There’s no such thing as an unremarkable day in anyone’s life. I began writing to record my time and place, to share it with my grandchildren and future generations.”

He encourages everyone to write. “Poetry can be created in short blocks of time; as little as 10 or 15 minutes is enough to capture an important memory, image, or experience. Over time, this can leave a substantial history for those who come after us.”

At age six, Roseland suffered an infection resulting in a serious hearing loss. Most writers would find this challenging, but Roseland considers it a blessing. “Not being able to hear well allowed me to be present without distractions, available to everything around me.”

After high school, Roseland went to South Dakota State University in Brookings, where he became student editor of Calliope, their literary publication. He transferred to the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, where he earned a master’s in sociology with a minor in statistics.

Roseland realized that, given his education, it was likely he would spend the rest of his life behind a desk. The idea of such a future did not appeal to him. He asked himself what he was good at doing. “I have a knack for pulling calves,” he admitted, with pride.

His dad offered him an opportunity to work the family ranch. He did a 180-degree turn. “I returned to the ranch in the 1980s, the farm crisis years. Great timing. It was reassuring to know that if things got too bad, I had a degree to fall back on. It gave me the courage to tough out the hard times.”

Roseland and his late first wife, Barbara, moved to the family ranch. She taught English in a nearby high school. They had two sons. It was Barbara who put together some of his poems and sent them to the Institute for Regional Studies in Fargo, North Dakota. These poems became his first book, The Last Buffalo (2006), which won the respected Wrangler Award in 2007. Barbara passed from multiple sclerosis in 2013.

A few years later, Roseland began searching for the UND friend who had introduced him to his late wife. “I found Julianne on Google. Barb and she were roommates at college. She’d become a psychologist, living on Maui. After a year of calls and emails, I convinced her to move back to South Dakota with me. I think sending her my books helped.” The couple married in 2019 and purchased a second home in Spearfish, in the northern Black Hills.

Roseland enjoys spending time in his Spearfish home when cows and crops permit, but he is still a full-time rancher. When the 72-year-old is asked about plans to step back from active ranching, he smiles, “How many retired ranchers do you know?”

Roseland describes poems as “little stories about what matters to us, stories that give us the ability to see into the hearts of others, to have others see into the truth of ours.”

Roseland’s ability to see into ordinary events in daily life has grown into a substantial body of work. Four of his seven published volumes have won national awards. In addition to the Wrangler Award for The Last Buffalo, Roseland has won the Will Rogers Medallion in Western Poetry three times: 2009, for A Prairie Prayer (2008); 2019, for Cowman (2018); and 2022, for Heart of the Prairie (2021).

Wanting to connect with local poets, Roseland joined the South Dakota State Poetry Society in 2008. He was elected President of SDSPS for three terms, stepping down in October 2022 to apply for the post of Poet Laureate.

In South Dakota, the SDSPS board recommends a new Poet Laureate based on an application process. Their recommendation then goes to the Governor for approval and appointment. The post has always been unpaid. Roseland approaches the responsibility of being Poet Laureate with enthusiasm. “I want to be an ambassador for poetry to all folks across South Dakota.”

Roseland credits the natural world as his first muse. He credits Walt Whitman for freeing poets from the confines of prescriptive verse. He admires Ted Kooser, whose freestyle poetic philosophy emphasizes ordinary, everyday subject matter.

Roseland’s work captures the character of rural plains people determined to make a life on challenging terrain. His descriptions of prairie landscapes and the natural world reveal the sacred relationship of the land to the wildlife it supports and those who are its stewards. His recent work calls attention to the impact of advances in agricultural technology and the need to conserve native grassland.

His poetry describes the experience of loss and celebrates the deep connections to community that sustain his family, friends, and neighbors. Roseland writes with frankness and respect about life in the wide open so valued by South Dakotans.

As Poet Laureate, Roseland regularly participates in a program called Poetry on the Road. Along with other SDSPS member poets and special guests, the entourage visited towns throughout South Dakota to give readings in 2023 and will continue throughout 2024. At each reading, an open mic is available to anyone who wants to share their poems.

Everyone is a poet at heart, Roseland believes. When choosing something to write about, he suggests, “Choose a subject that’s personal, look for things that strike you. Describe it and boil it down to its essence. Your emotion will give you the proper words. The hardest part of poetry is ownership of words and making them behave. When I sit down to write, 80 percent of the lines are in my head. It’s the other 20 percent that’s my challenge. A poem may come differently to you. Trust your own process, keep tweaking until it feels 100 percent true.”

“Writing groups are good for validation of your writing. Networking, shoptalk, give you connections. Follow your heart. Don’t conform for no reason, leave the door open. Look for commonalities.”

Roseland loves ranch work and has never regretted his career choice. He still found time to coach youth and high school wrestling for over 30 years. Roseland is proud of having coached his sons and two of his four grandchildren in wrestling. Now, as Poet Laureate, he coaches potential poets.

To Roseland, our lives will be enriched if more people are encouraged to write and share important memories that form the foundation of our regional culture. He asks, “How can we know who we are? How can we identify our values without knowing the stories, the history of how we got where we are? All of our stories are important.”

Roseland explains, “Learning about the values of others teaches us about our neighbors and about our world. This is a primary value of writing and publicly sharing poetry. When we share our poems with others, we create a community of shared values. Communities have power to put their common values into action. Some of us are more interested in community action than others. Yet, the most introverted soul, who writes from the heart about what they value, may find that a single poem of theirs, read at a small gathering, was an important source of inspiration for someone who did act on that shared value.”

The best way to understand Roseland’s work is to let the new Poet Laureate speak for himself. Here is one of Roseland’s best-known poems, his reflections on what led to writing it and the public response.

A Prairie Prayer

Here, on this arc

of grass, sun and sky,

I will stay and see if I thrive.

Others leave. They say it’s too hard.

I say hammer my spirit thin,

spread it horizon to horizon,

see if I break.

Let the blizzards hit my face;

let my skin feel the winter’s freeze;

let the heat of summer’s extreme

try to sear the flesh from my bones.

Do I have what it takes to survive,

or will I shatter and break?

Hammer me thin,

stretch me from horizon to horizon.

I need to know the character

that lies within.

I want to touch a little further

beyond my reach,

for the something that I seek.

Only then let my spirit be released.

Roseland’s Commentary: “A Prairie Prayer” is a poem that first occurred to me in my 30s. It was the result of lines that popped into my head when I was frequently, frantically, trying to get things done. You’re fighting the elements, blizzards, mud, when spring calving happens. You’re always under the gun. A lot of things are happening at the same time. In summer, the work has to get done, because you only have so much time.

I had an opportunity not to do that, to get a desk job that had its own constraints and problems but was more of an eight-hour-a-day job. The job I chose was sunup to sundown and frequently past that. But I wanted to do it. I came back voluntarily, because a lot of the people I admired the most were the older guys I knew, those who had gone through tough times and made it. I wondered if I had what it took to make it. Could I go through a whole lifetime and still be standing? Could I know the character that lies within me?

That’s what “A Prairie Prayer” is about. It’s my prayer. Do I have what it takes to survive? Can I handle the elements, can I handle everything that’s thrown at me? In the end, am I still standing? This is a poem that has struck a lot of other people. Those who stayed in South Dakota did so because they wanted to, it was their choice.

The biggest connection to others I’ve become aware of is that they too, feel connected to this place. They too, have felt this struggle and have stayed because they wanted to, and they too, are still standing. It’s kind of like a brotherhood, a sisterhood, a commonality.

People’s response to “A Prairie Prayer” has been powerful because they too, want to find out if they have what it takes. We know we are one of each other. The words were all there in my 30s, but it took until my early 50s to write them down. I’ve faced a lot of history in South Dakota–seasons, droughts, blizzards–and I still want to be part of it. Even with all the adverse conditions, we all still want to be part of it.

Click through to read South Dakota’s Prairie Poet Laureate, Part II, including four more of Roseland’s best-received poems and his commentary on their inspiration and community impact. Roseland can be scheduled to read for your class, group, or event through the SDHC Speakers Bureau.

Learn more about humanities programming in South Dakota by signing up for SDHC e-Updates!